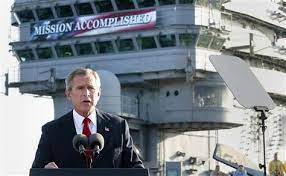

Twenty years ago this coming Sunday, on March 19, 2003, the United States launched an attack on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, upon the expiration of a March 17 U.S. ultimatum to Saddam to leave the country. The Iraq War (as we now remember it) was unlike its short and successful 1991 predecessor (« Operation Desert Storm »). This war (officially named « Operation Iraqi Freedom ») was destined to be long and demonstrably less successful. The war was undertaken after Iraq was declared to be in breach of a U.N. Security Council Resolution which prohibited « stockpiling and importing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).” But no such weapons were ever found. And, while Iraqi forces were overwhelmed quickly and Baghdad fell a mere five weeks after the invasion began, the U.S. quickly found itself involved in a long-term occupation, for which neither the military nor the American people were quite prepared. Whereas the 1991 war had been undertaken by – or at least with the support of – a significant coalition of countries, the 2003 war was, with some significant support from the U.K., nonetheless predominantly an American affair, and one which was widely unpopular outside the U.S.

Most Americans probably supported the war when it began in 2003. There was, however, some significant – and perhaps prescient – opposition. Barack Obama opposed the war, which could have killed his future political prospects. Instead, thanks to the war’s ultimately disastrous outcome and widespread American disillusionment with the war, it proved an advantage against his primary opponent, Senator Hilary Clinton, who had of course, initially supported the war, as had most of the political elite. In the end, the Iraq War came to be seen as a folly of Vietnam-like proportions. It discredited the hitherto ascendant « neo-conservative » ideology. It discredited personally the « neocons » who had promoted it and unleashed an anti-interventionist, neo-isolationist spirit and movement, the problematic consequences of which are very much with us today. Much as the catastrophic economic failure of 2008 led to a « populist » reaction against the George W. Bush Administration and the Republican Establishment, that same Administration’s failure in Iraq and the complicity of the bipartisan Foreign Policy Establishment led to a « populist, » neo-isolationist reaction against globalism and alliances, one result of all of which was the 2016 election of Donald Trump. Another related result is the various contemporary manifestations of anti-interventionism in regard to Russia’s aggressive war against Ukraine – which in different degrees and in varying ways among its different proponents can be characterized as anti-NATO, anti-Western, anti-democratic, pro-appeasement, and even pro-Russian.

Of course, the war did prove the neocons wrong and did warrant a rethinking of the directions American foreign policy had been taking in the post-Cold War and the post-9/11 era. I suppose that should be the outcome of any failed war. Vietnam immediately comes to mind. But there is also a kind of narrow historical monism that typically takes over these discussions. When I was in college, and Vietnam was the centerpiece of all foreign policy debates, there was always the Munich analogy to invoke in support of the American adventurism in Vietnam or to try to rebut if one was in opposition. The thing about Munich, however, was that the analogy only worked within certain assumptions. Obviously, if the Sudetenland was indeed just part of Hitler’s long-term plan to achieve military supremacy in Europe – as in retrospect, we can have no doubt that it was – then, of course, it was morally and politically wrong to « appease » Hitler at Munich. If, on the other hand, it was (as could be plausibly claimed at the time) just the final step in reuniting all the German-speaking peoples in one Reich, well then what was really the right response? Remember Chamberlain’s unease about getting involved in a « quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing. »

Like the Munich analogy, the Iraq War analogy is easily abused. Indeed, some right-wing pundits in their eagerness to appease Putin invoke it so constantly that one wonders if they even know that the U.S. have ever fought other wars, with other outcomes. Bush’s Iraq misadventure is a cautionary tale against interventionism and « democracy-promotion » – just as Munich (now that we know beyond doubt what Hitler’s purpose was) is a perpetually cautionary tale against appeasement of aggression. Both are true. Neither by itself answers every question.

But let there be no mistaking – regardless of what the appeasers proclaim – the Russian aggression represents a real threat not just to Ukraine but to all of Europe and what remains of western civilization. This is not a « quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing. » And the contemporary neo-isolationists in our midst are for that reason in their own way exacerbating that threat.

P.S. One good thing to have come about as a result of the Iraq war was Generation Kill – a seven-part HBO miniseries that aired from July 13, 2008, to August 24, 2008. It was based on Evan Wright‘s 2004 book of the same name about his experience as an embedded reporter with the U.S. Marines 1st Reconnaissance Battalion during the initial invasion and occupation of Baghdad. I believe it is still available on HBO On Demand. It remains well worth watching!

Photo: President George W. Bush prematurely proclaims « Mission Accomplished, » May 1, 2003