Back in the day, the standard course on « Modern Political Theory » might stretch back as far as Machiavelli and More, Luther and Calvin. It might likewise project forward including Mill and Rawls or, more daringly, Marx. But, whoever else might be read, it would almost inevitably include the trinity of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, with Hobbes and Locke presented either superficially as alternatives or more seriously as complementary. Unlike Rousseau, Hobbes and Locke were what we have bee accustomed to call liberals – Hobbes, « the only one, perhaps, still worth reading, » in the judgment of John Gray, author of The New Leviathans: Thoughts after Liberalism (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023).

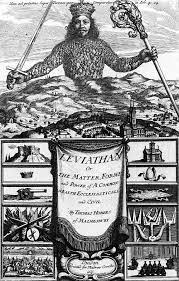

English Enlightenment philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) published Leviathan in 1651. Its famous frontispiece (above) illustrated the benefits of the powerful sovereignty Hobbes advocated as necessary for human flourishing, as against the alternative natural state of war, in which life is « solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. » Hobbes’ sovereign power would serve to protect individuals from their fear of one another, facilitating cooperation and consequently « commodious living, » without classical political philosophy’s presumption either of natural human sociability or of some natural human purpose, « no finis ultimis (utmost aim) nor summum bonum (greatest good).

What Gray calls New Leviathans « are not Leviathans Hobbes would recognize. » Unlike Hobbes’s goal of « securing its subjects against one another and external enemies, » post-liberal New Leviathans « aim to secure meaning in life for their subjects, » replacing « a liberal civilization based on the practice of tolerance » with « engineers of souls, » which « promise safety » but « foster insecurity » – « a return of the state of nature. in artificial forms. »

The bulk of Gay’s book is largely concerned with examples of those post-liberal New Leviathans. Gray argues « an era of delusion in the West » followed the collapse of communism – « the theory of globalization, a mix of dubious economic theory with millennial political fantasies. » Far from an end of history, Gray sees a move « Back to an epoch that is classically historical » – a world « like that of the past, with disparate regimes interacting with one another in a condition of global anarchy. »

Particularly interesting are his analyses of the Soviet Union and of post-Soviet Russia, where the Orthodox Church has now « come to occupy the ideological niche filled until recently by the Communist Party. » He deems it unsurprising « that when the communist secular theocracy collapsed it was followed, under Putin, by a more authentically theocratic regime. »

Closer to home, he bemoans a « hyperbolic version of liberalism » in the West, which attempts « to emancipate human beings from identities that have been inherited from the past, » resulting in « an artificial state of nature among self-defined identities. » Such hyper-liberal « woke » ideology functions « to deflect attention from the destructive impact on society of market capitalism, » prioritizing identity questions over economic conflicts. « Woke hyper-liberalism is Puritan moral frenzy unrestrained by divine mercy or forgiveness of sin. »

He is comparably harsh in his assessment of the modern politics of rights, which I have long perceived as modern liberalism’s peculiar problematic. The goal of Hobbesian logic, « is not agreement, but modus vivendi. » When society is divided by such questions as abortion, assisted stoning, sexuality, and gender, « the attempt to resolve them by inventing and enforcing rights » – as Roe v. Wade so infamously attempted to do in 1973 – « is fatal to peace. »Inevitably, his analysis leads to the contemporary rise of « populism » – an ambiguous term « used by liberals to refer to political blowback against the social disruption produced by their own policies. »

In contrast to what the modern liberal West has wrought, Gray recalls how « Hobbes believed human beings need limitation as much as they need freedom, » which was early modern political theory’s retrieval of the Christian message that « sinful humankind must live by divine guidance. »

It is easy to look at the increasingly chaotic character of modern politics – both the collapse of a short-lived international order and the collapse of domestic political consensus – and recognize some of what Hobbes was warning about. Since Hobbes – under the influence of the likes of Locke and Rousseau and the liberal and radical traditions they spawned – it has been possible to aspire to a more liberating resolution of Hobbes’s war of all against all, different from either Hobbes’s liberal solution of supreme sovereignty or the classical socio-political paradigm Hobbes’ rejected. Instead, the evolution of Leviathan into modernity’s monstrous New Leviathans challenges that aspiration.

Hence, the perennial relevance of Hobbes’ Leviathan, regardless of who else appears in the modern political theory pantheon.