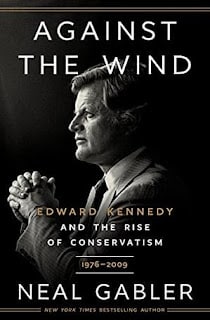

A couple of years ago, American journalist and author published Catching the Wind: Edward Kennedy and the Liberal Hour 1932-1975 (Crown, 2020), which I commented on here on February 26, 2021. Now he has completed the story of the greatest of the Kennedy brothers with his mammoth (1280 pages!) sequel, Against the Wind: Edward Kennedy and the Rise of Conservatism 1976-2009.

The first volume told the story of how an otherwise unqualified 30-year old younger brother of a dynastically oriented president unexpectedly became – over the course of 47 years – one of the stars of the U.S. Senate and one of the greatest advocates for liberal causes in American politics. In an overly rich, overly privileged, overly entitled family of unbridled, arrogant ambition, « Ted » Kennedy became the one most truly admirable figure from that family and from that time. The first volume prefigured a detailed and ambitious personal and political biography, and the second volume does not disappoint.

In the first volume, Gabler retold the familiar account of Ted’s rise through the lens of his marginal status within the family itself – the youngest child, from whom little was expected in comparison with his star-quality brothers, but who unlike them developed precisely those personal empathetic qualities which enabled him to connect naturally and effectively with people and in the end made him a better and more effective politician than his higher stature brothers – « Teddy, the most empathetic of the Kennedys, in part because he was the most disrespected of the Kennedys. »

In this volume, Gabler examines the radically changed circumstances against which Kennedy’s later Senate career enfolded – the American turn to the right, reflected in the disastrous election of Ronald Reagan and all that has followed since (and anticipated in the disastrous presidency of Jimmy Carter), as well as the deterioration in American political institutions, not least Ted’s beloved Senate itself.

Once Kennedy finally disappointed himself and many of his fans by not becoming president and instead turned his attention full-time to the Senate, his story really takes off. « Ted Kennedy, however, had come to the Senate with a different agenda, a different attitude. He was no less desirous than his brothers of getting things done, no less desirous of making a difference. But when he got to the Senate, Ted Kennedy had patience. » For fans of legislative process, Gabler seems to recount virtually every detail of virtually ever bill Kennedy was connected with (one reason why the book is so monumentally long).

But ultimately this is not a process book. Gabler’s account of Kennedy’s legislative successes and failures finds its fullest meaning against the background the transformation of the political landscape from the highpoint of liberalism in the mid-1960s to liberalism’s gradual exhaustion in the 1970s. Gabler interprets the end of the liberal era in primarily moral terms. « Trying to stir a liberal conscience in the electorate, as Bobby had tried to do in 1968, was not a road to success in 1980 either. In a survey conducted after the campaign, three political scientists found that the ‘Senator’s compassion for the less fortunate, long considered to be an attribute, generated more criticism than praise.’ The moral moment had long since passed. » Gabler’s concept of the moral moment may be the leitmotif of the entire book.

And, of course, closely connected with the loss of liberalism’s moral authority, would be the loss of a traditional constituency, illustrated so well in the account of the politically and personally bruising Boston battle over school busing, with which this volume begins. Somehow, in Kennedy-friendly Massachusetts, Kennedy kept getting reelected, but elsewhere other liberals were less fortunate.

Nonetheless, Kennedy never gave up. The most dramatic example of that, of course, was his commitment to providing adequate health care for Americans. As the dying Kennedy said to the new President Barack Obama: « “This is the time. Don’t let it slip away.” That time, it didn’t.

Obviously, the personal cannot be separated from the political – especially in a self-conscious political dynasty like the Kennedys. So Gabler fills us in on Kennedy’s long-drawn out marital troubles with his first wife, Joan, his complex relationships with his children especially his son Patrick, and his successful second marriage and the benefits (both personal and political) which followed from it. Inevitably, we re-experience various Kennedy family tragedies – among them the particularly problematic episode surrounding Ted and his nephew William Smith.

As in the first volume, Gabler does not shy away from the importance of religion in Ted’s personal story. So we hear, for example, a lot about Ted as a daily Mass attender. In the famous letter, he wrote to the Pope at the end of his life, which President Obama delivered on his behalf, Kennedy wrote that the gift of faith he had received from his mother had “sustained and nurtured and provided solace to me in the darkest hours. I know I have been an imperfect human being, but with the help of my faith I have tried to right my past.” And, even as he asked the Pope to pray for him, he recalled the causes that had motivated him so passionately: “I want you to know, your Holiness, that in my 50 years of elected office I have done my best to champion the rights of the poor and open doors of economic opportunity. I’ve worked to welcome the immigrant, to fight discrimination and expand access to health care and education. I’ve opposed the death penalty and fought to end war. Those are the issues that have motivated me and have been the focus of my work as a U.S. Senator.”

Few have been able to claim a nobler legacy.