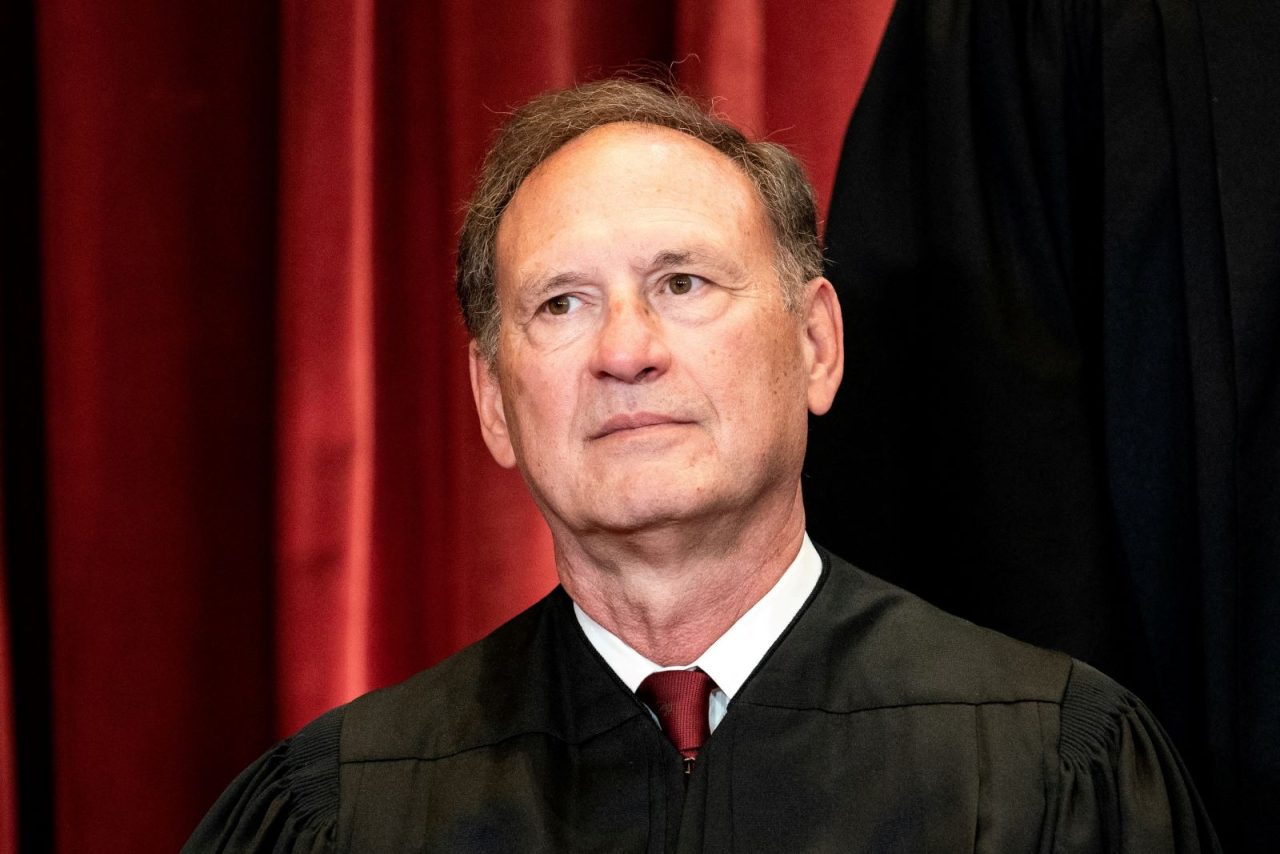

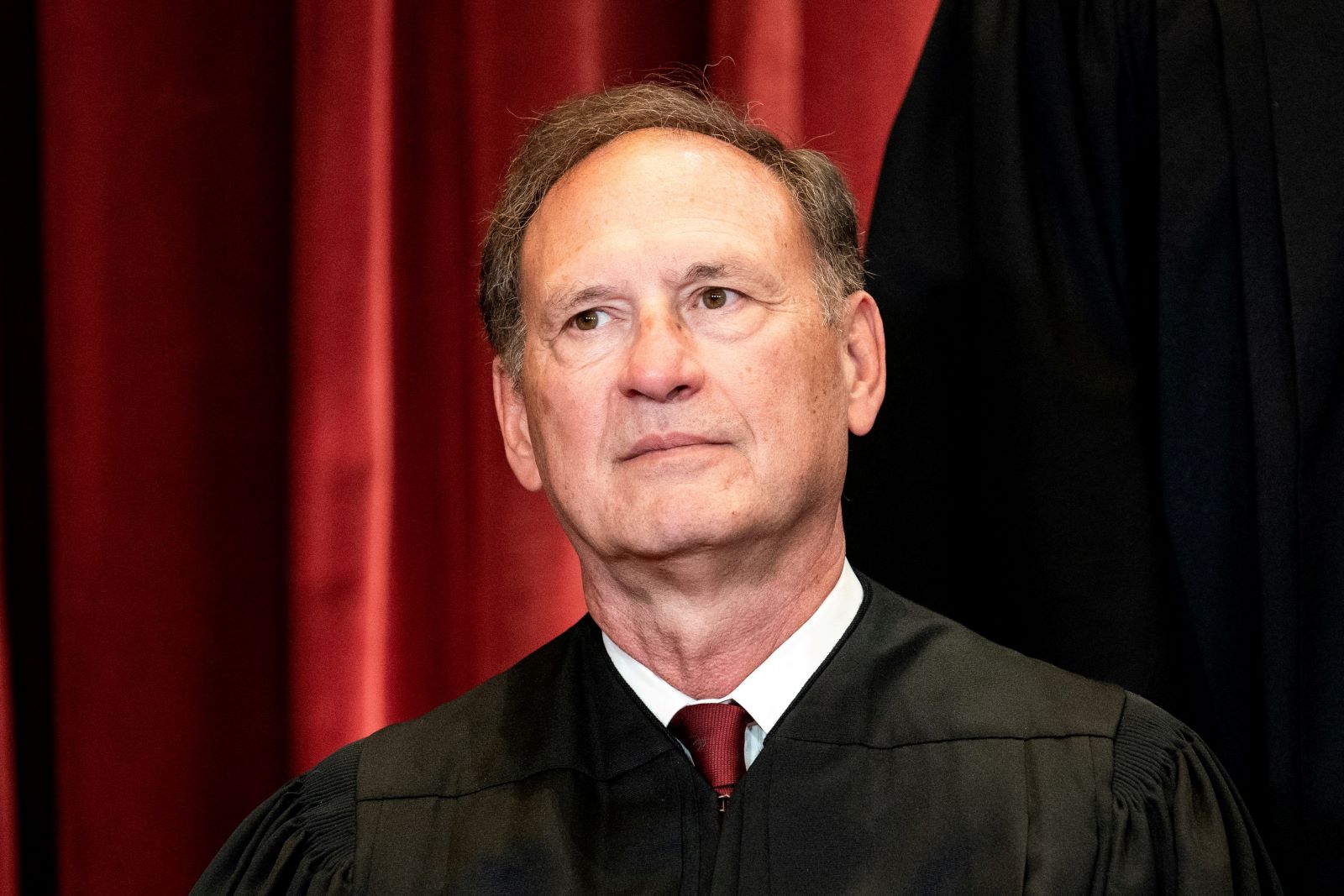

WASHINGTON (CNS) — Justice Samuel Alito told a group of law students in Washington that he is always mindful that the rulings he and his colleagues on the U.S. Supreme Court issue “are not abstract discussions” and “have a real impact on the world.”

Alito made the remark in a question-and-answer session Sept. 27 after delivering an address at the Columbus School of Law at The Catholic University of America to kick off the school’s new “Project on Constitutional Originalism and the Catholic Intellectual Tradition.”

As honorary chair of the project, the Catholic justice launched its fall speaker series with an overview of what it will explore.

In offering his thoughts, he raised a lot of questions, saying he hoped they would spark discussions among those involved in the project and lead to a better understanding of the topic.

“What I want to try to do is sort of set the stage for the work that will follow,” he said, “so you can think of me sort of like a member of the stage crew at a theater who comes out and turns on the lights perhaps and sets up the scenery, so that the stage is ready for the players who will provide the main event.”

So “what is constitutional originalism?” he asked. “You can’t explore the relationship between constitutional originalism and the Catholic intellectual tradition if you don’t understand what constitutional originalism is.”

“It is the theory that the Constitution should be interpreted in accordance with its original public meaning,” he explained, as opposed to the “living” constitutionalism theory, which in general advocates interpreting the U.S. Constitution broadly in accord with current societal views.

The theory of originalism “is controversial” and “has often been thought — correctly or incorrectly — to be associated with conservatism,” Alito noted.

“Does constitutional originalism apply only to the Constitution of the United States or does it apply to other constitutions as well, such as foreign constitutions and state constitutions?” Alito continued. “Does it apply to all interpreters of the U.S. Constitution or only to a particular category of people who interpret the Constitution — namely federal judges?”

“If it applies only to federal judges, why is that so?” he said. “And if it is not just a doctrine for federal judges … does it apply to all government officials who must abide by the Constitution? Does it apply in the same way to members of Congress and presidents?”

He traced the modern theory of originalism to the 1970s.

“There was not at some point in time a big constitutionalism seminar attended by a lot of brilliant people who debated the subject and after that they split up, and some were originalists and some were living constitutionalists and some were pragmatists and so forth,” Alito said. “It was nothing like that. … It grew up in a particular concrete historical moment.”

“Originalism arose as a reaction to the way constitutional interpretation had been carried out by the Warren court during the prior decade,” he said, referring to Chief Justice of the United States Earl Warren. He served as the nation’s 14th chief justice from 1953 to 1969.

“By the end of the 1960s, the perception had arisen in many quarters that controversial Warren court decisions, particularly in the area of criminal justice, had been based not on the Constitution but on justices’ personal policy preferences,” Alito said.

“For the record: I am not saying those decisions were wrong or right. I’m just noting historical fact that was the perception in some quarters at that time.”

“One attraction of originalism was that it promised to impose clear limits and thus prevent judges from using constitutional decision-making as a vehicle for imposing their own policy preferences on the country,” he said.

His late colleague Justice Antonin “Nino” Scalia — whom he said he misses “very much” — was “a pioneering originalist,” he said, who believed originalism “is there to prevent” the potential for judges to impose their own views.

“But what happens when a case concerns a situation that could not have arisen when the relevant constitutional provision was adopted?” Alito asked.

That comes up “most clearly when new technology is involved,” he said, like violent video games.

Do laws to keep children from viewing these games violate the First Amendment?

He pointed to the case Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, which challenged a 2005 California law banning the sale of certain violent video games to children without parental supervision. The court struck down the law in 2011.

“Needless to say, there were no violent video games in 1791 when the First Amendment was adopted, so what should be done?” Alito asked. “Should we look for the closest parallel, like the description in books?”

There are “some pretty gory scenes in books,” like the horrific slaughter of warrior after warrior in “The Iliad” by Homer, he noted, and there is “all sorts of violence not appropriate for children” in “Grimm’s Fairy Tales,” like when Hansel and Gretel shove a witch into an oven.

“Does that decide the question?” he asked.

Determining how the Catholic intellectual tradition intersects with constitutional originalism will be a challenge for those involved in this new project, Alito remarked.

This Catholic tradition spans more than two millennia, “extending back to the pre-Christian era back to Aristotle and Cicero,” he said.

“It covers a broad range of subjects,” he said, and it will be necessary to focus on a narrow slice, like Catholic thought about the role of the state or Catholic thought about the law.

Speaking less than a week before the Supreme Court opened its new term, Alito told the students of an idea he had proposed to his fellow justices.

“Know how when you go to baseball game and the player comes to the plate and a song is playing? I have told my colleagues we should have the same (thing) when we take our seats.”

– – –

Follow Asher on Twitter: @jlasher