« When, in 1843, I first read in the catechism of the Council of Trent the doctrine of the communion of saints, it went right home. It alone was to me a heavier weight on the Catholic side of the scales than the best historical argument which could be presented. … The body made alive by such truths ought to be of divine life and its origin traceable to a divine establishment: it ought to be the true church. The certainty of the distinctively Catholic doctrine of the union of God and men made the institution of the church by Christ exceedingly probable. » [Isaac Hecker, “Dr. Brownson and Catholicity,” The Catholic World, November 1887.]

The doctrine of the communion of saints had a decisive impact upon young Isaac Hecker’s spiritual discernment, leading him into the Catholic Church the following year. That Isaac Hecker (1819-1888) recalled this so vividly, so many years later, is an indication of how important the doctrine of the communion of saints really is in the Church’s life.

Uniting past and present, the communion of saints permeates the Church’s worship, and punctuates the Church’s calendar with a multitude of feasts and memorials of saints, culminating today in this great annual celebration in honor of all the saints. That all refers in particular to that part of the communion of saints known as the “Church Triumphant” – not just the multitude of « canonized » saints officially recognized as such by the Church, but all the holy men and women, known and unknown, who have attained the goal for which we all aim, and who now praise God for ever in heaven. Living now for ever with God and praising him for ever in heaven, the saints – that great multitude from every nation, race, people, and tongue [Revelation 7:2-4, 9-14] – help us by interceding on our behalf, uniting their prayers with ours, imitating Jesus himself, our Risen Lord who lives forever to intercede for us [Hebrews 7:24-25].

The regular reference to – and invocation of – the saints, not just today but in every Mass everyday, signifies our union (as the still struggling Church on earth) with the triumphant Church in heaven. It reminds us that the Church’s mission in this world is to mirror that heavenly community of angels and saints – and so transform the world according to the hope that is Jesus Christ’s great gift to his Church and the Church’s gift to the world.

Deliberately celebrated on the day after Halloween, All Saints Day celebrates the hope that replaces fear, exemplified in the lives of the saints and experienced by us in our continued relationship with them – a communion which challenges that great opponent of human hope an destroyer of human relationships, death, by connecting us not only with the saints already in heaven but with all who, according to the traditional language and prayer of the Church, « have gone before us with the sign of faith » (qui nos praecesserunt cum signo fidei).

Hence, around the end of the first millennium, as a sort of sequel to All Saints Day, the Church added All Souls Day on November 2, a day devoted to urgent prayer on behalf of all who, having died, are now still being purified from the consequences of their sins.

In his 2013 book Mercy: the Essence of the Gospel and the Key to Christian Life, Walter Cardinal Kasper called the doctrine of purgatory « a sign of this infinite mercy and forbearance of God for those who have not fundamentally and decisively decided against him. … Ultimately, it is the condition that results from encountering our holy God and the fire of his purifying love, which can only passively endure and through which we become altogether prepared for full communion with God. … At the same time, it offers the community of the faithful the possibility, in solidarity, to intercede for the deceased before God. »

Here in the northern hemisphere, thoughts about the end come quite naturally at this time of the year, as the sun rises a little later every morning and sets a little earlier every afternoon. Amidst withered leaves and barren branches, there is a melancholy sense of time passing by as yet another year draws to a close. The universe, as we know it, did not always exist and will not always exist. However distant the day, it is doomed to end. Less distant, there is the individual – but no less definite – death of each one of us. The human condition of alienation from God through sin makes mortality seem the ultimate frustration. Perhaps, that may help to explain modern secular society’s increasing inclination to downplay death, even to the point of failing to provide complete religious funerals for the deceased. In contrast, in the Church’s calendar, both the month of November and the season of Advent, which immediately follows it, have traditionally focused on our end, as an inevitability which we humanly fear, but for which we wait with the hope made possible for us by Christ. Christian hope causes one both to treat all of life as a preparation for a good death and not to neglect the duty of prayer for those who have gone before us. Hence, how we think and speak about Christian hope regarding the end and the eternal fulfillment of God’s purpose for creation is fundamental for a coherent Christian faith.

The great autumn triduum of Halloween, All Saints, and All Souls challenges us to face our fears and contemplate the mystery of death – but to do so in faith and hope. For if we believe that Jesus died and rose, so too will God, through Jesus, bring with him those who have fallen asleep [1 Thessalonians 4:14].

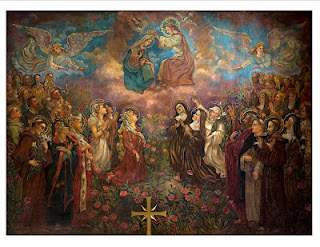

Photo: Mural of the Crowning of Mary, Queen of Heaven by William Laurel Harris (1870-1924), featuring Saints Casimir, Clare, Francis of Assisi, Dominic, Luke, Teresa of Avila, Catherine of Siena, Mary Magdalen, Augustine, Monica, Anthony of Padua, Bernard, Philip Neri, Alphonsus Liguori, and John of the Cross, Saint Paul the Apostle Church, NY.