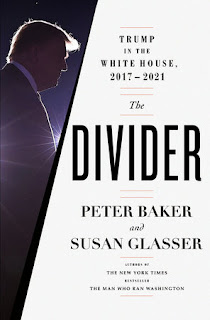

The Divider: Trump in the White House, 2017-2021 (NY: Doubleday, 2022), by NY Times Chief White House correspondent Peter Baker and his wife The New Yorker‘s « Letter from Biden’s Washington » author Susan Glasser, is but the latest in the seemingly endless journalistic retellings of the (still ongoing) Trump saga. And it is still ongoing – as the authors frankly warn in their epilogue, even making the warning comparison with Napoleon exiled at Elba, from which as we all know he returned to Paris for one final fling as Emperor. But, whereas Napoleon was definitively defeated the second time, and there was never any doubt that the other Powers would coalesce to defeat him decisively, there can be no assurance of either in Trump’s case.

In the veritable forest of Trump-era books, Baker and Glasser’s excels in its enormous detail and effective argument. The case for the damage Trump has done is clearly and convincingly made, the result of hundreds of interviews and references to texts, emails, and other documentary records. And it reads like the frightening adventure story that it is. While undeniably focused on Trump and not in any sense a wide-ranging history of the era, it fills us in on all sorts of related, otherwise significant events that occurred during Trump’s reign – for example, Jared Kushner and the development of the Abraham Accords.

Inevitably in a book about Washington, this is also a book about staffers and politicians, the obsessive lust for relevance which animates so many of them and which has helped guarantee Trump’s complete takeover of the Republican party – and the occasional opposition that prevented things from getting even worse, for example, « for the first time since Richard Nixon’s final days, a defense secretary who saw his job as constraining the president of the United States rather than empowering him. » On the other hand, « Republicans were now defined by their choices about whether and how to accommodate their leader and his strongman style. »

As its title indicates, this is also very much a book about how Trump « profited from » America’s internal schisms « and widened them. » Much of the book details the « intense and toxic » Trump White House. « It was personal, it was political, it was philosophical. And from the very start, it was all-consuming. The polarization that Trump encouraged in the outside world, he fostered inside his own building too. »

Trump’s private reality radically differed from the public realities of his predecessors – for example, his « idée fixe that had not evolved since the 1980s: the conviction that the country had been taken for a ride by foreign allies and adversaries alike. » Such nationalistic resentments reflected the very personal resentments and grievances of « a man never accepted by the exclusive set whose approval he so craved. »

At the time, Trump’s ideological emptiness had briefly caused me to wonder whether he might actually be able to forge a novel and successful path. Baker and Glasser muse on what might have been. « Trump more than any president in generations had come to the White House without strong party affiliation or philosophical moorings and in theory might have bridged the capital’s divides had he chosen to. »

Of course, one cannot write about Trump’s presidency and its unprecedentedly dysfunctional personnel situation without considering the family component. We learn about the emotionally fraught relationship between the two Donalds, senior and junior. « When Ivanna gave birth, he objected to sharing his name with his newborn son. ‘What if he’s a loser?’ he asked. » During the troubled time of his parents’ divorce, Don Jr. reportedly yelled a this father, « You don’t even love yourself. You just love your money. » Don Jr. eventually joined the family business, but the relationship remained troubled until the campaign, when he « eventually became a leading surrogate for his father. More than anyone else in the family, he channeled the culture war grievances that animated his father’s campaign crowds » – becoming, in Roger Stone’s words, « the voice of undiluted Trumpism. »

At the opposite end are the favorite child, Ivanka, and her husband, Jared Kushner, who « believed they were the only ones who truly understood Trump and had his best interests at heart. » Baker and Glasser show that Trump seems to have been originally a bit ambivalent about Jared and Ivanka’s roles in the administration, how they were a thorn in the side of presidential staffers (and, apparently, the First lady), and how they were among the first to accept reality and detach themselves from the post-election Big Lie. « Whatever Trump said, neither Jared nor Ivanka believed then or later that the election had been stolen. » They « had no interest in being part of the show. »

In a presidency which numbered so many unprecedented and traumatic moments, culminating in the unprecedented if by then predictable refusal to recognize the results of the election, the pandemic stands out as perhaps both the most representative illustration of Trump’s dysfunctional presidency. Baker and Glasser describe what they call « classic Trump, » who « had some of the world’s smartest scientists, the most experienced disaster relief managers, and highly educated economists whose job was to prepare for moments like this working for the government, but he did not trust them. He was looking for someone to tell him how to get out of this situation without having to do what they were telling him to do. »

After a particularly crazy pre-Christmas meeting about overturning the election results, Trump himself is quoted int he book as saying, « in 200 years there probably has not been a meeting in this room like what just happened. » What a wonderfully self-aware recognition of what the whole experience of Trump’s presidency was for the country!

Having recounted in detail the events surrounding the end of the Trump presidency, including his second impeachment, Baker and Glasser leave us with this warning about a possible Trump second term, when many of the restraints that ostensibly inhibited his first term would be gone. « Trump would not make the same mistake of hiring advisers who stood up to him – he would choose matadors like Mark Meadows not obstacles like John Kelly. He would pursue vengeance against his enemies. He would politicize the courts, the Justice Department, and the military. He would challenge allies and seek common cause with autocrats. We know he would do these things because those are exactly the things that he did and said for all four years of his first term in the presidency. »

At least we cannot claim not to have been forewarned!