The fantastic new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, takes us back to one of the most formative periods in British history, the 118-year reign of the Tudor dynasty, the last five exclusively English monarchs (before the Scottish King James VI claimed the crown of England as the great-grandson of a Tudor princess). As we all once learned – whether in school or from various Showtime and Starz dramatic series – Henry Tudor, a Lancastrian claimant to the throne defeated the Yorkist King Richard III (himself a usurper at his Yorkist nephew Edward V’s expense) at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 and began the eventful era of Tudor rule as Henry VII. In school, we were once taught that Henry VII’s subsequent marriage to Elizabeth of York ended the Wars of the Roses by uniting the two competing dynasties, and began a new era of post-medieval stability for England.

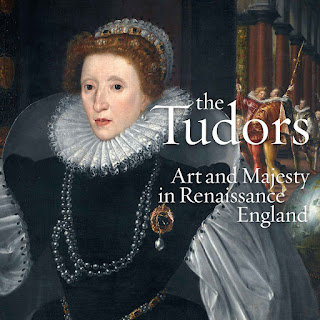

In fact, however, the Tudors’ claim was never completely secure. Hence, the second Tudor king’s obsession with securing a male heir, which resulted in the mother of all Brexits, Henry VIII’s secession from the Catholic Church. With the new complication of religion, the succession crisis only intensified. Henry VIII’s three legitimate heirs all sat on the throne, and the last of them, Elizabeth, reigned long enough (1558-1603) and gloriously enough to preside over England’s « Elizabethan Age – and to be portrayed in the ad for this exhibit (photo above). But all three died childless, and the Tudors gave way to the Scottish Stuarts (also descended from Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, the common ancestors of all British royalty ever since).

Still the Tudors continue to fascinate – both for their personal problems and for the centuries of religious strife they unleashed, as well as for the modern commercial kingdom (and eventually empire) which became their legacy.

Delayed by the pandemic, The Tudors is an appropriately impressive exhibition, adequate to the bold grandeur of the Tudors and their era and to the widespread fascination in this country with the Tudors and their era. (Perhaps the American fascination is only appropriate, since the founder of the Tudor dynasty was the first to claim some sort of sovereignty – albeit at the time mostly nominal – over any part of North America, a sovereignty that has expanded and contracted under his successors but still survives in part, if again only mostly nominal.)

The exhibition reflects the high courtly fashions of the Renaissance, a time when Europe was still (at least until the Reformation) really united culturally, and it revels in Renaissance splendor. Tudor England hosted an international community of artists, some 100 of whose famous and not so famous works are on display in this exhibition. We see Tudor propaganda in tapestries and aristocratic genealogies, and ecclesial splendor in liturgical vestments. And, of course, we see portraits of the five Tudor monarchs and of other contemporaries, some of whom most of us may have never heard of. We see the most famous martyrs of the Tudor era – a familiar portrait of Saint Thomas More and a bust of Saint John Fisher, the leading statesman and the only bishop to remain religiously faithful against the depredations of the Tudor tyrant.

England under the Tudors was a small, only modestly significant kingdom, in the process of transforming itself into a major commercial and naval power and eventually an empire. (It is perhaps no accident that it was the second Tudor monarch who chose to act on the curious claim, rex est imperator in regno suo!) The artistic creativity of the era both reflected and reinforced the claims and aspirations of an unsurprisingly insecure but amazingly successful dynasty.