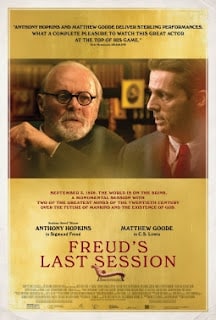

I used to go to movies much more often. Now I seldom see new films. Finally, however, one 2023 movie which I have been really wanting to see has recently become available for rental via YouTube. Freud’s Last Session, based on an earlier stage play of the same name, depicts a fictional meeting between the founder of psychoanalysis, Dr. Sigmund Freud (Anthony Hopkins) and author C.S. Lewis (Matthew Goode) on September 3, 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany, and just 20 days before Freud’s own death.

Dr. Freud, of course, had escaped from Nazi-occupied Vienna a little over a year earlier thanks to the efforts of various friends and allies (notably Dr. Ernest Jones, U.S. Ambassador William Bullitt, and Princess Marie Bonaparte). It is known that Freud did meet with an unidentified Oxford don near the end of his life. That could possibly have been Lewis. We will likely never know, but the opportunity for this fictionalized account obviously suggests itself. (Given the extent of Friend’s then terminal illness, one wonders how vigorous a conversation could have taken place in September 1939, but again this is fiction.

The storyline of the film is that Freud, a long-term Jewish atheist, and indeed one of modernity’s most effective exponents of the case against religion, objected to Lewis’ rejection of atheism in favor of Christianity; and so the two met to debate the question of the existence of God. In the course of their discussion, other subjects also arise, among them Lewis’ own lingering traumas from his childhood and from World War I. Meanwhile, we also get to meet Freud’s famous daughter and child psychologist Anna (Liv Lisa Fries), on whom Freud was very obviously dependent at that point. We also meet her lesbian partner, Dorothy Burlingham (Jodi Balfour), a relationship in constant conflict with Freud’s possessive attitude toward his emotionally dependent daughter. Despite the film’s title and its implied emphasis on the debate between the two men, much of the film focuses on Anna and her complicated relationship with her father, who had famously abandoned the canons of psychoanalysis in analyzing his daughter himself.

The opening scenes set the stage in the context of the panicked atmosphere in London on the first official day of war, including an air-raid warning which at one point causes the two men to take refuge in, of all places, a local church, where Freud correctly identifies the statue of Saint Dymphna, patroness of the mentally ill. Otherwise, most of the men’s interaction takes place in Freud’s London home, within which Anna seems to have done her best to replicate their Vienna home, and which reflects Freud’s long-term interest in religious artifacts. Indeed, he describes himself as « a passionate disbeliever, who is obsessed with belief and worship, ancient beliefs and worship, yours [Lewis’s] included. »

Freud was, of course, a dying man at this point, which adds further pathos to the story and its seemingly unresolvable debate about God. « Death, » Freud acknowledges, « is as unfair as life. » Freud’s life represented the ideal of scientific rationality, which just cannot make room for religion, no matter how interesting it may find the pre-rational in human existence. Lewis, for his part, asks in exasperation, « Why does religion make room for science, but science refuses to make room for religion. » His question remains unanswered, on the screen as in real life.

In the end, the two men part – presumably as friends. but the religion question remains unresolved, as it perhaps inevitably is in this life. Both men remain essentially unchanged, which may be the film’s honesty and its virtue.