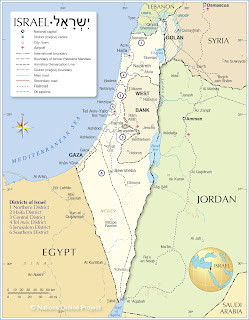

The the chimera commonly called the « two-state solution » has haunted middle-eastern politics for as long as I have lived. Actually longer. The famous UN Partition Plan was adopted on November 29, 1947 – almost four months before I was born. In some alternative universe, had the Arab states been willing to accept the existence of a Jewish state, had they therefore accepted the UN Partition Plan, an Arab state would have been created on part of what was then the British League-of-Nations Palestine Mandate, along with a Jewish state (and a Jerusalem Corpus Separatum).

On February 16, 1948, however, the UN Palestine Commission reported to the Security Council that: « Powerful Arab interests, both inside and outside Palestine, are defying the resolution of the General Assembly and are engaged in a deliberate effort to alter by force the settlement envisaged therein. » By May, when Britain finally withdrew from its Palestine Mandate, and Israel declared its independence, five Arab states (Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Jordan) attacked the former Palestine Mandate territory, although Jordan limited its invasion to that part of the territory that the partition plan assigned to the Arab population, now known as Palestinians, territory Jordan would take for itself.

The 1949 Armistice agreement left Israel with a little more territory than it had originally been assigned by the partition plan, plus West Jerusalem. The rest of the Arab-assigned territory (the « West Bank », including East Jerusalem, and the « Gaza Strip ») were occupied by Jordan and Egypt respectively. Presumably, those two countries could have created the independent Arab state that the UN had earlier envisioned, but they did not choose to do so. Nor does there seem to have been much international pressure for them to do so. The Jordanian occupation of the West Bank and the Egyptian occupation of Gaza continued until Israel’s victory in the 1967 war, when Israel replaced Jordan and Egypt as the occupying power.

In the aftermath of the Israeli victory and occupation, Palestinian nationalism became a sufficiently powerful force, such that Jordan and Egypt effectively relinquished their claims to the territories they had recently occupied and eventually made their own separate peace treaties with Israel.

Meanwhile, an international consensus formed around the idea of a solution in the form of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. The 1993 Oslo Accord, which established limited Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza, represented the apogee of aspirations for such a « two state solution. » The closest Israel and Palestine ever came to such a solution was probably the plan which Yasser Arafat rejected in 2000. Since then, while the « two state solution » has remained official U.S. policy, it has become increasingly unachievable in reality, and less and less of a priority for Israel’s Arab neighbors, which have increasingly pursued policies without real reference to Palestinian aspirations. Indeed, the growing threat from Iran seems to have inspired Saudi Arabia and other Arab states to reconsider their inherited rejection of Israel in favor of accommodation bordering on alliance, with little to show for the Palestinians.

Yet the modern world is a world of nation-states. So, in the modern world, the normal aspiration of a territorially definable ethno-national group is achieving its own national state. Witness the proliferation of new states in the former Soviet Union and the former Yugoslavia after the end of the Cold War! The state of Israel itself is a testimony to the reality that only by having a state of its own can a people properly protect themselves from aggression and even the threat of extinction. It is thus only natural and normal that the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza should aspire to a nation-state of their own. Unfortunately for them, their rejection of every previous opportunity to make a real peace and thus achieve something like a nation-state has had the result that the territory available for such a state has shrunken significantly from what they originally could have gotten in 1947. Meanwhile, a history of hostility has understandably made it harder and harder for Israelis to imagine a Palestinian nation-state next door which would not pose an unacceptable threat to their security, a realistic fear which has been exploited by Israel’s current government to pursue a policy of increasing intransigence, paralleling Palestinian intransigence.

If there remained any doubt of the incorrigibility of such Palestinian intransigence, last Saturday’s barbarous sneak attack on Israel by Hamas has undoubtedly confirmed it. (It is, of course, possible in principle to distinguish between Hamas and the ordinary Palestinian population. On the other hand, there is little evidence to suggest that that population does not support Hamas’ goals, and it is worth recalling that Hamas became the government of Gaza as a result of popular election by the local Palestinian population.)

This is not the first war between Israel and Hamas terrorists. And there is no guarantee that it will be the last. There is no guarantee that Israel will be able to defeat Hamas as decisively as it obviously needs to. Nor is it clear what victory over Hamas would ultimately look like or accomplish. Would such a victory suddenly dispose the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank to seek permanent peace with Israel? Not likely. Would it end all possibility of Palestinian terrorism? Not likely. Would it bring peace and stability to the rest of the Middle East? Very unlikely. Would it cause Iran to abandon its aspirations to regional hegemony and its seemingly ineradicable hatred of Israel? Absolutely unlikely.

But one outcome that seems so likely as to be near certain is that any « two-state » solution will be even less likely than at any time since it was first proposed in 1947.